Intestinal Nerves and Serotonin in Gut Function

The Body’s Second Brain

The enteric nervous system (ENS) is a large and complex network of nerves that manages the activity of the gastrointestinal (GI) system. These nerves talk to your real brain and also get help from your body’s stress system, immune system, and hormones. But even without help, the ENS can work on its own—that’s why some doctors call it the body’s “second brain.”

The ENS has over 100 million nerve cells from your mouth all the way to your bottom. These nerves use chemicals like serotonin and dopamine to send messages. These same chemicals help with your mood, too. Most of the serotonin in your body—and about half of your dopamine—are found in your gut! That’s why some IBS medicines work by helping these chemicals do their job better.

When the digestive system is not working properly, symptoms like diarrhea, constipation, vomiting, and abdominal pain can occur. These responses all involve the actions of the enteric nervous system.

Inside the digestive system, there are groups of nerves called neural circuits that are found in the walls of the intestines. These nerves help control how your digestive system works—things like how food moves through your gut and how much fluid or chemicals your body releases to help with digestion. These nerves can get directions from the brain, but they can also work on their own.

This special system of nerves is called the enteric nervous system (ENS), and it has some amazing abilities:

- Sensing Danger and Nutrients: The ENS can tell when harmful things like bacteria or viruses enter the gut. When this happens, the body might react by throwing up or having diarrhea to protect itself. The ENS can also sense good things, like nutrients in food, and start the digestion process.

- Helping Food Move: The ENS helps the intestines know when to mix up food or move it along so it can be digested and leave the body when it’s done.

- Controlling Secretions: The ENS can tell muscles and glands in the gut when to speed up or slow down. This helps make sure everything is working just right.

All of these actions are controlled by the nerve cells in the intestines. But when someone has a disease that causes swelling or inflammation in the gut—like Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis—the way these nerves work can change. This can cause problems like belly pain, diarrhea, or other symptoms.

New research shows that inflammation can change how the nerves respond. This can make the gut more sensitive or mess up how it moves food. Sometimes, these changes can last a long time—even after the inflammation is gone. This might be part of what causes long-lasting digestive problems in some people.

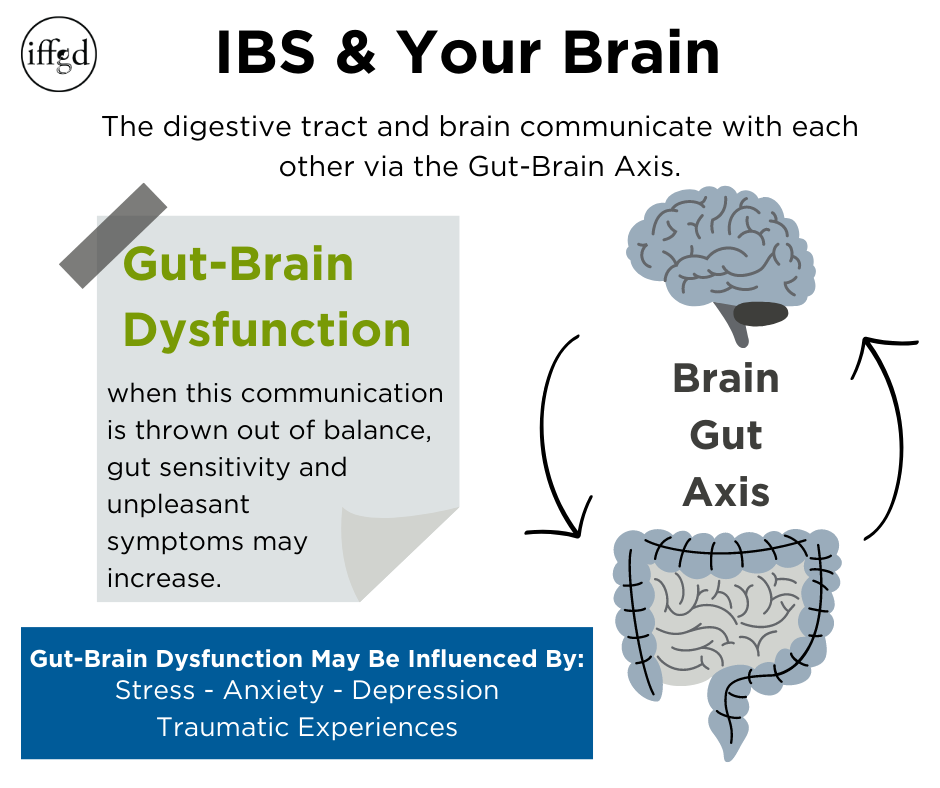

The Gut-Brain Axis

As stated above neural circuits found in the intestinal wall can be controlled by the brain. The Gut-Brain Axis (GBA) is a communication system between the digestive tract and the brain. This pathway is bi-directional, meaning the brain communicates with the gut, and the gut also communicates information to the brain.

The GBA involves communication between several systems in the body:

• Nervous System – Playing a role in nearly every aspect of our health, the nervous system is involved in automatic activities such as breathing, and in complex processes such as thinking, reading, remembering, and feeling emotions.

• Endocrine System – Consisting of all the body’s different hormones, the endocrine system regulates all biological processes in the body.

• Immune System – This network of biological processes protects your body from diseases.

Gut-Brain Dysfunction

When the Gut-Brain Axis (GBA) is out of balance, normal sensations—such as food moving through the digestive tract—that would typically not be noticed or considered bothersome, can be experienced as unpleasant symptoms. In other words, the gut can be more sensitive than normal. A number of factors that can influence Gut-Brain dysfunction:

- Stress– Stressful events, as well as long-lasting or recurring stress, can lead to dysregulation of the Gut-Brain Axis. Stress can also result in changes in gut motility and permeability.

- Early Life Stress and Traumatic Experiences – Patients with IBS report higher rates of physical, emotional, or sexual abuse and general early life trauma than non-IBS patients. Early life stress is associated with more severe and difficult-to-treat GI symptoms. The impact of early life stress is also associated with IBS patients’ increased stress (cortisol) response and decreased resilience or ability to bounce back. As a result, untreated early life stress can make it harder for patients to cope with their IBS symptoms once they appear.

- Anxiety and Depression – Patients with IBS report higher than normal rates of anxiety and depression. IBS patients also report higher rates of somatization, which is a tendency to experience stress through physical symptoms. The presence of anxiety or depression is associated with increased GI symptom severity and poorer mental health outcomes, which lead to a higher level of interference in a patient’s quality of life.

- GI Symptom-related Anxiety, Hypervigilance/Attentional Bias – Some IBS patients who do not have general anxiety may still experience anxiety triggered by their GI symptoms. Bothersome GI symptoms can lead to anticipatory anxiety, worrying that a serious IBS incident is about to strike, bringing with it discomfort, urgency, and (possibly) embarrassment. While understandable, it can lead some patients to become stressed and overly focused on physical symptoms. This stress can then cause more, and stronger, IBS symptoms, which will, in turn, cause the patient to become even more focused than before.

- Visceral Hypersensitivity – Many patients with IBS report a tendency to experience discomfort or pain in response to normal bowel functions. This is known as visceral hypersensitivity. It is believed that in IBS patients, the ENS nerves send stronger pain signals to the brain in response to activity within the GI tract. Muscle contractions moving food through the GI tract, or normal gas patterns, are now perceived as discomfort or pain. Brain-imaging studies demonstrate alterations in the way the brain responds to gut sensations and is associated with increased sensitivity.

The GBA also communicates with the gut microbiome, which includes all the bacteria in the intestines.

IBS and Your Gut

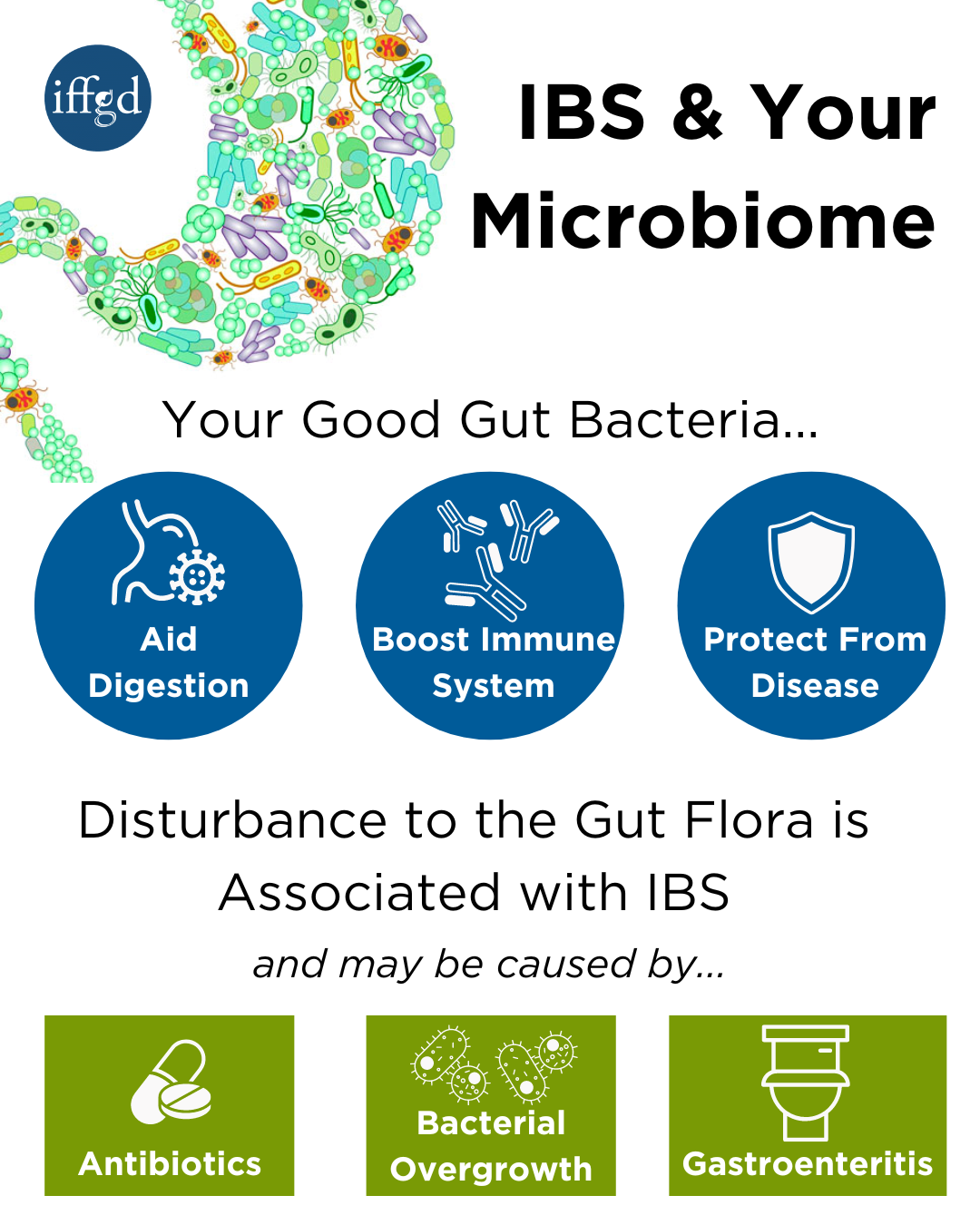

Trillions of bacteria, both good and bad, exist within our gut and complete important functions including:

- Protecting against bacteria that cause disease

- Maintaining the immune system, and

- Helping with digestion

Good intestinal bacteria are often referred to as the gut flora (or microbiota) which help form our gut microbiome.

The gut microbiome is the diverse combination of microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, and protozoa that are found in a person’s digestive tract. Research has found that patients with IBS have changes in the gut microbiome, which can influence intestinal inflammation and pain.

How does the disturbance of our gut microbiome relate to IBS?

There is evidence to support that disturbance in the bacteria that populate the intestine may have a role in the development of IBS. This evidence is summarized as follows:

- Antibiotic use, well known to disturb the flora, may predispose individuals to IBS

- Some people may develop IBS suddenly following an episode of stomach or intestinal infection (gastroenteritis) caused by bacteria (a condition called post-infectious IBS or PI-IBS)

- A very low level of inflammation may be present in the bowel wall of some IBS patients, which could have resulted from an abnormal interaction with bacteria in the gut

- Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) may be associated with IBS

- Altering the bacteria in the gut, with antibiotics or probiotics, may improve symptoms of IBS

- In PI-IBS some people develop IBS-type symptoms following an episode of gastroenteritis, while most others recover completely. PI-IBS represents a clear link between exposure to a bacterial infection (such as from contaminated food or water) and IBS in those who seem especially at risk.

Conclusion:

Our bodies are complicated and when imbalanced, our bodies will be negatively impacted. Growing evidence suggests that IBS may result, at least in part, from a dysfunctional interaction between our gut-brain axis (GBA) and our gut microbiome.

Because there are numerous factors that may contribute to a patient’s symptom experience, treatment plans need to be personalized and tailored to that patient’s needs. For some patients, simple diet and lifestyle modifications may be all that is needed to relieve symptoms.

For patients with severe symptoms, a more comprehensive, integrated approach (formulated in collaboration with your gastroenterologist, dietitian, and GI health psychologist) is often the most effective treatment approach.

Adapted from IFFGD Publication 133- Gut-Brain Axis and IBS, IFFGD Publication 163 Current Diagnostic Approach to IBS, and 266 Intestinal Nerves and Gut Function